Image created by AI

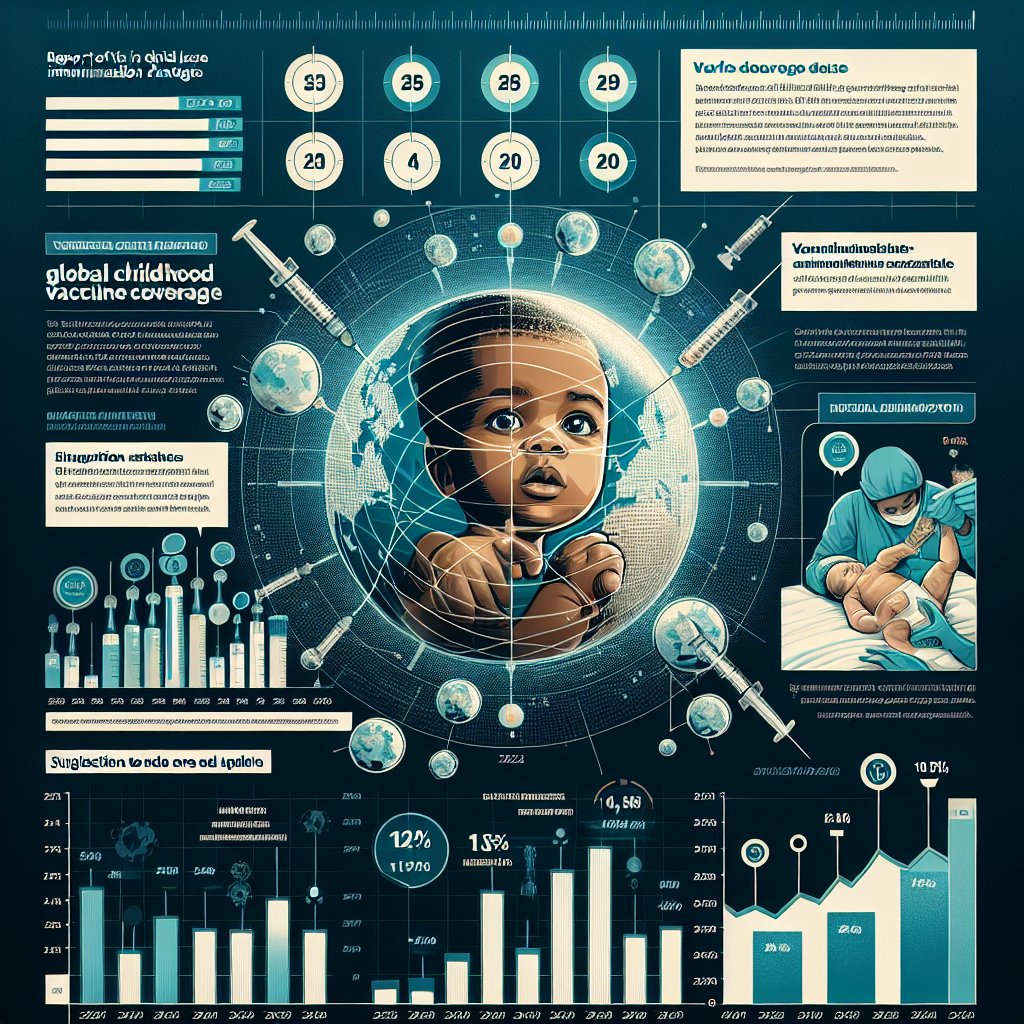

Dismal Decline in SA Childhood Immunisation Calls for Robust Action

The World Health Organization, alongside UNICEF, has raised an alarm with the stagnation seen in global childhood vaccine coverage, spotlighting a particularly concerning trend in South Africa. The coverage, which has failed to rebound to pre-pandemic levels, left 2.7 million additional children at risk in comparison to 2019, with South Africa witnessing a worrying decrease in immunisation metrics for diseases like diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and measles.

A profound dip in South Africa's vaccination coverage was noted in the report with the coverage of the first dose of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTP1) declining to 81% in 2023 from 87% in 2022. An even more significant decrease is evident in the measles vaccination coverage, which dropped from 86% to 80% in the same timeframe.

The accuracy of the data provided in the report could be arguable, with concerns raised by Professor Shabir Madhi about the reliance on administrative data which might not accurately reflect the ground reality. The WHO and UNICEF methodologies estimate coverage by dividing the doses administered by the estimated target population, which may not account for doses that are wasted or not utilized.

Despite the discrepancies in data collection methods, the report's estimates align reasonably well with local data in South Africa, suggesting that the nation's vaccination effort is indeed faltering. Dr. Haroon Saloojee emphasizes that while fluctuations in immunisation coverage are common, the recent decline is not to be overlooked.

The situation worsens with the increase in zero-dose children, with South Africa ranking 6th worst in the African region—a staggering decline from its 13th position in 2022. This hints at profound underlying issues within the national healthcare system and its delivery of immunisation programs.

Professor Madhi draws attention to South Africa's shortfall in reaching its own targets—only seven of 52 districts achieved full vaccination for children under one year. He pinpoints the shortfall to the primary healthcare system, which is deemed dysfunctional, reflecting a failure to implement well-established vaccination programs effectively.

Haroon Saloojee and Shabir Madhi both concur that a reevaluation of South Africa's immunisation strategy is imperative. This includes streamlining governance structures, enhancing the monitoring of real-time data, safeguarding vaccine funds, and revamping strategies that have not yielded results in the past two decades. Furthermore, an effective national immunisation strategy, bolstered by governmental leadership and adequate resources, is needed to guide improvements through 2030.

The National Department of Health, despite acknowledging queries on addressing the dire need to improve immunisation coverage, has yet to provide an official response or comment on the matter.

While the global report rings alarm bells for several countries, South Africa's sharp decline in childhood vaccination coverage calls for immediate and vigorous public health interventions to remedy a potentially perilous backslide in child health metrics.