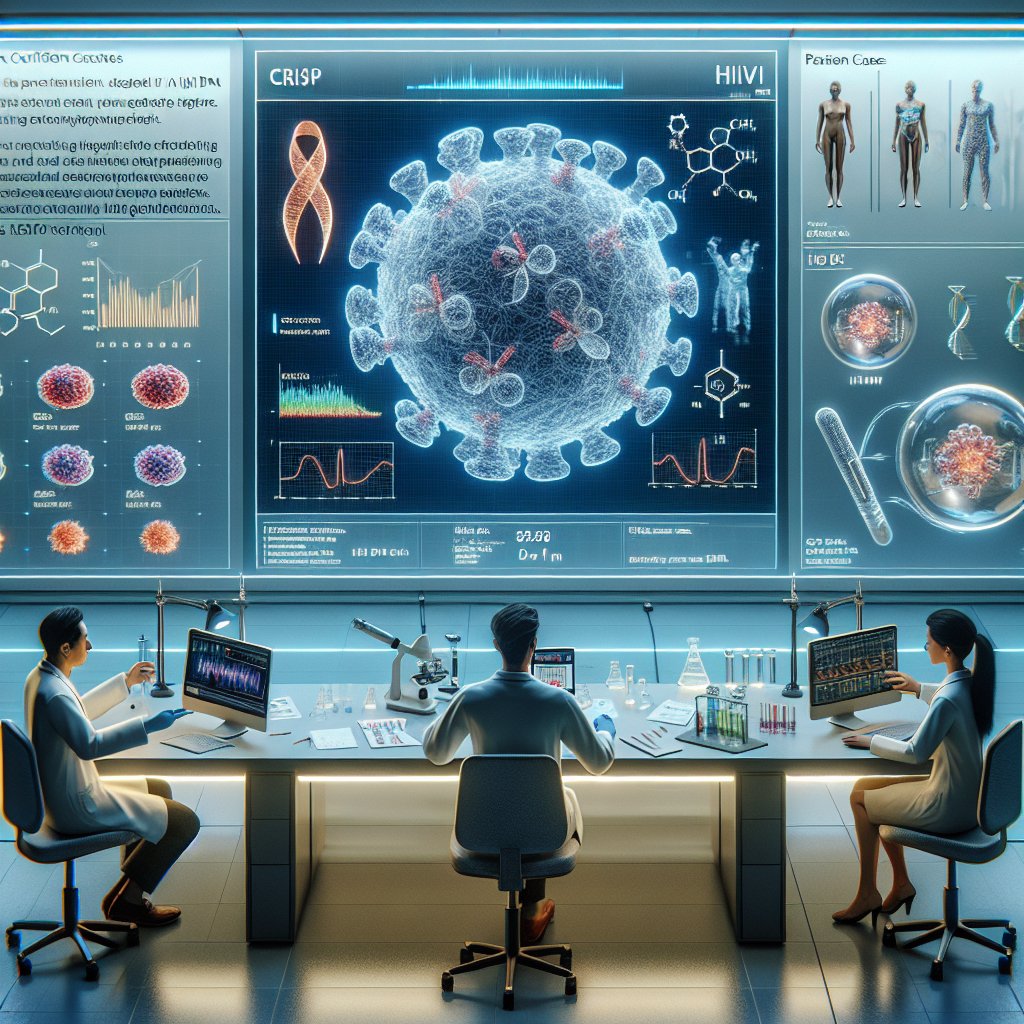

Image created by AI

Groundbreaking Gene-Editing Technique Shows Promise in the Fight Against HIV

In a significant scientific breakthrough, researchers at the University of Amsterdam have reported initial success in eradicating HIV from infected cells using the Crispr gene-editing technology. This novel approach, which operates like molecular scissors by cutting DNA to remove or deactivate harmful sections, has the potential to revolutionize the treatment of HIV by completely eliminating the virus from the human body.

Crispr technology, which earned the Nobel Prize for its inventors, has been identified as a potential game-changer in battling numerous genetic diseases. For HIV, which currently has no cure and is treated with antiretroviral therapies that can only suppress the virus, the gene-editing technique could mark the beginning of the end of the virus's hold on human health. Current treatments are effective at managing HIV, but they leave behind a reservoir of dormant infected cells, capable of reigniting the infection if treatment is halted.

The findings were presented by the research team at a medical conference, where they cautioned that despite the positive results, their work is still in its infancy and cannot be labeled as a definitive cure for HIV at this stage. Experts around the globe, including Dr. James Dixon from the University of Nottingham, echoed this sentiment, emphasizing that more research is crucial to ascertain the safety and effectiveness of this method.

Parallel efforts at Excision BioTherapeutics also endeavor to use gene editing to combat HIV, and recent clinical observations have shown that three patients have experienced no major side effects after 48 weeks of treatment.

However, the overarching challenge — as Dr. Jonathan Stoye from the Francis Crick Institute points out — is the eradication of HIV from all potentially infected cells within the human body and the understanding of long-term side effects that might emerge due to this intervention.

Historically, a few rare cases have provided a glimpse into what an HIV cure could look like. Aggressive cancer therapies in certain individuals have inadvertently cleared the HIV infection – these are known within the medical community as 'sterilizing cures.' Yet, this method is not applicable as a widespread treatment strategy for HIV due to the aggressive nature of cancer treatments and their associated risks.

The implications of this latest research are monumental, not only for the 38 million people worldwide living with HIV but also for the future management of other viral infections. Here lies a beacon of hope that with ongoing research, dedication, and refinement, a complete cure for HIV might one day become a reality.