Image created by AI

Innovative Study Suggests Bright Lights on Surfboards May Prevent Shark Attacks

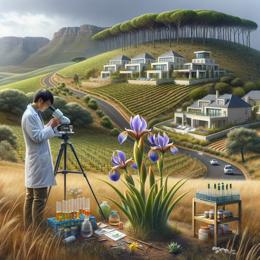

In what may be a surprising twist to conventional wisdom, a recent study spearheaded by Australian scientists from Macquarie University, including biologist Laura Ryan, suggests that affixing bright lights to surfboards might reduce the risk of shark attacks. This novel research was carried out in Mossel Bay, South Africa, known for its population of great white sharks.

Contrary to what one might assume, the research indicates that great whites, which are known for confusing surfers with seals from below due to the similarity in their silhouettes, could be deterred by the use of bright horizontal LED lights on surfboards. The study, published in the acclaimed journal Current Biology, noted that the lights appear to disrupt the shark's perception of potential prey on the ocean's surface.

The researchers employed seal-shaped decoys adorned with different LED light configurations and towed them behind a boat to observe the sharks' reactions. It was found that decoys with brighter and horizontally oriented lights had fewer interactions with sharks, suggesting that sharks are less inclined to attack when their typical visual cues are distorted.

The findings could not only help surfers and kayakers but could also signal a shift in shark mitigation strategies. Countries like Australia, which have extensive shark management systems involving drones, nets, and tagging, could benefit by supplementing their methods with less invasive and more eco-friendly options.

This research has exciting implications but also notes the necessity for further investigation to understand the effects of this approach on other shark species like bull and tiger sharks, which exhibit different predatory patterns. Additionally, the potential for this technology to be integrated into water sports equipment such as kayaks alongside surfboards is now a step closer, as Ryan and her team are developing prototypes.

The urgency of finding effective shark deterrents is underscored by historical data documenting over 1,200 shark incidents in Australia since the late 18th century, with great whites accounting for 94 fatal encounters. The quest for safeguarding human life while respsecting marine ecosystems continues, with this study contributing a potentially significant piece to the puzzle.