Image created by AI

Zuma's Hold Over IEC Sparks Concerns

In a move that echoes the echoes of South Africa's fraught political history, former President Jacob Zuma appears to have crafted a cunning and potentially dangerous overture towards asserting further control over the country's electoral processes. His hand in the finalising of the MK party's constitution—a document that practically positions Zuma at the helm, empowered to rule by decree—poses serious scrutiny upon the limitations of the checks and balances that are meant to safeguard the Electoral Commission of South Africa (IEC).

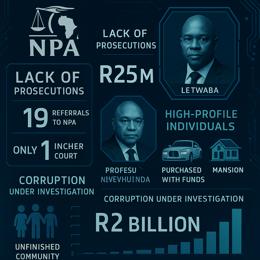

This development raises questions about the utilization of funds allocated by the IEC for political party functioning, which are carved out ostensibly to engage public participation in the political realm. The breadth of interpretation allowed by the IEC's guidelines on the usage of such funds gives ample room for manipulation, especially in regions like KwaZulu-Natal where coercion and intimidation are not alien to politics.

The IEC system did not just crash, but it was deliberately and systematically aborted. What the public doesn't know is that MK was at 55 % nationally, when this was done. There's evidence that Bheki Cele was at the IEC server room when this happened.

— Indoda Yamaqiniso🇿🇦🇷🇺🇨🇳🇮🇷🇨🇺🇻🇪🇨🇩 (@i_yamaqiniso) June 4, 2024

MK and EFF | ANC NEC |… pic.twitter.com/H3jwQu9svz

The cunning realignment of the MK party to a system that layers patronage upon already existing structures speaks volumes about the entrenched nature of clientelism in South African politics. This not only sustains the hearty salaries and pensions at the top of the ladder but also perpetuates a cycle of fealty that cripples the very notion of dissent within party ranks.

Political theorists have been delving into the concept of "destituent power," opposed to "constituent power," suggesting mechanisms within political movements that aim not to create but discreate or disrupt existing structures. South Africa, with its history of upheaval and reconstruction, now stares at the face of what could be another exercise of destituent power—a scenario where existing systems are consistently challenged or eroded as seen in various government sectors and in the behavior of some political actors.

The effects of the ANC's cadre deployment as a manifestation of destituent power are all too evident in the inefficiencies and lacunae in service delivery and governance. This is further compounded by the sharp and often confrontational stance taken by certain figures against the judiciary, an integral pillar of constitutional democracy.

Despite the malcontents, one can't overlook the silent majorities and their interactions with the ANC. The muted enthusiasm for the ANC at the polls and the discussions on a Government of National Unity (GNU) signal a populace that may be wary of overt political engagement, yet possesses the power to reactive substantial shifts in governance—a subtle, yet potent exercise of destituent power.

The future of South Africa's political landscape sits on a fulcrum balanced precariously between the memory of its constituent power-driven revolution and the realities of a destituent present that both hinders progress and offers the chance for new visions in governance. As Zuma's influence, whether direct or symbolic, looms over the intricate dance of power and populism, South Africa must grapple with the idea that the revolution it birthed now requires another kind of revolution to sustain the moral and constitutional integrity of the nation.