Image created by AI

The Moon as Earth's Ark: Scientists Propose Cryogenic Preservation of Species

In a remarkable fusion of conservation and space exploration, scientists have put forth a visionary proposal to ensure the perpetuity of Earth's biological heritage. Titled "Lunar Pits Could Preserve Historic Traces of Ice and Host Polar Resources," this paper was published in BioScience by a group helmed by researchers at the Smithsonian, striking a chord with both environmentalists and space aficionados alike.

This audacious concept envisages the Moon as a celestial vault, where Earth’s vulnerable species could be stored cryogenically. Contrasting with energy-dependent preservation methods on Earth, this biorepository would utilize the Moon’s frigid, shadow-veiled craters for passive cryopreservation. Mapped at the poles, these craters sustain perennial darkness, driving temperatures down to a life-sustaining -410°F (-246°C).

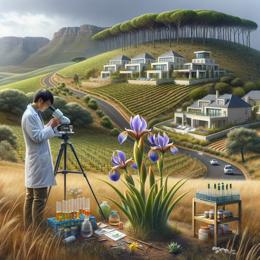

The Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute's own Mary Hagedorn, a seasoned cryobiologist and the lead author of this compelling paper, envisions an initial focus on Earth’s most endangered species. Eventually, the team hopes to encompass an extensive array of Earth’s flora and fauna. Hagedorn accentuates an ethos of collaboration, seeking partnership to navigate the complex web of challenges and potentialities posed by the project.

Parallels to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway are clear. The lunar biorepository is seen as a celestial counterpart, a safeguard against earthly vicissitudes. Svalbard's brush with peril in 2017, amidst a flood caused by permafrost melt, serves as a haunting harbinger of potential catastrophes exacerbated by climate change.

Plant cells, comfortable in Arctic climes, contrast sharply with animal cells that necessitate an otherworldly -320°F (-196°C) for preservation. On Earth, achieving this requires a trifecta of liquid nitrogen, electricity, and monitoring – commodities that could be compromised in dire global landscapes. This moon-based repository eschews such fragile dependencies.

The scientists have cast their eyes on the lunar substrate as a bulwark against cosmic radiation, contemplating the construction of subterranean vaults or edifices with lunar rock façades. This forward-thinking proposal, however, acknowledges the requisite extensive research into the effects of radiation on frozen biomaterial as well as the implications of microgravity environments.

Beyond a mere contingency, the lunar biorepository presents itself as a stellar adjunct to Earth-bound conservation efforts, potentially aiding in interstellar voyages. It's a testament to our acknowledgment of life’s singularity and sanctity.

Notwithstanding the enthusiasm, the proposal has been met with measured skepticism from the wider scientific community. Experts like Rob Brooker and Sally Keith voice concerns regarding the allocation of resources, postulating that the project's ambition and expense could overshadow and detract from immediate conservation needs on Earth. They underscore the pressing global biodiversity crisis and question if the mission to secure moon-based preservation could inadvertently eclipse the essential conservation happening, or necessary, on terra firma.

In the scheme of things, this proposition begs a rich dialogue amongst conservationists, policymakers, and the public alike. It offers an avenue for groundbreaking technological innovation while posing philosophical inquiries about our priorities as a steward of Earth's living mosaic.