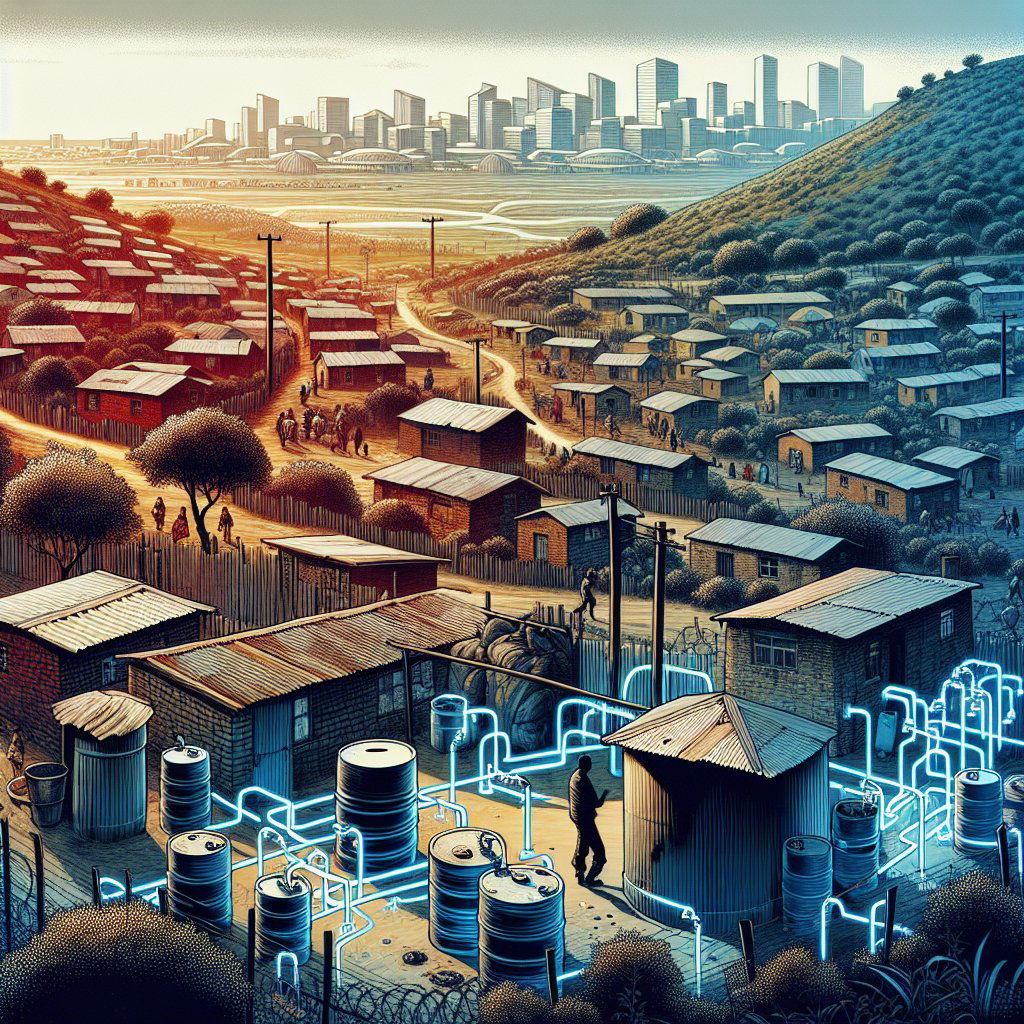

Image created by AI

Families in Santa Village Face Uncertain Future as Eviction Looms

In the heart of Mpumalanga, an air of despondency envelops the makeshift landscapes of Santa Village, an area taggling with the prospect of eviction. The residents, many of whom have called this informal settlement near Ackerville their home for decades, are now locked in a legal battle with the Emalahleni Local Municipality, which contends that the establishment of their dwellings was unauthorized and that the land is unfit for human habitation.

The case of Santa Village is representative of a broader issue within South Africa, where informality and the pursuit of shelter often collide with the legal and planning frameworks of municipalities. Approximately thirty years ago, pioneers of Santa Village erected the first structures in what was then mere bushland. Now, streetscape reveals a mix of humble brick houses and resilient zinc shanties, a testament to the community's will to build their homes despite lacking formal approval.

To the hundreds of villagers like Dudu Kunene, this entangled warren of streets is more than an informal settlement; it's the backdrop to their lives, the setting where they've raised families and fostered kinships. With the municipal axe hovering over their existence, resignation is tinged with defiance. The community claims that promises of formalization and infrastructural development have fallen by the wayside, and without proper substitution housing offered, the threat of eviction notices cripples their spirit. Residents are even more aggrieved by court adjournments which have delayed proceedings, exacerbating an already tenuous situation.

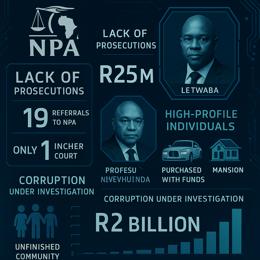

The Emalahleni Local Municipality, under the stewardship of municipal manager Humphrey Sizwe Mayisela, maintain their stance, asserting that after conducting a feasibility study, they concluded that the land is indeed inappropriate for habitation and that relocation is justified. The controversy lies not only in the impending destruction of homes but also in the procedural aspects; residents question when the municipality recognized their existence and what efforts were made toward a feasible resolution.

Water scarcity and electricity woes have long plagued the villagers, with communal taps and illegal electrical connections being the lifeline for these underserved residents. Still, even in these trying conditions, a sense of pride in their resilient community prevails. As the day of reckoning draws closer, with the following court hearing set for March 7, the Santa Village inhabitants prepare for the courtroom confrontation.

Santa Village showcases the complexities of dealing with unauthorized settlements. The fight between the Emalahleni Local Municipality and the residents goes beyond legal rhetoric—it's a clash between livelihoods rooted in place and governance bound by regulation. As the community braces for what may come, South Africa looks on, grappling with the broader implication of this eviction and the fate of similar settlements in other parts of the country.