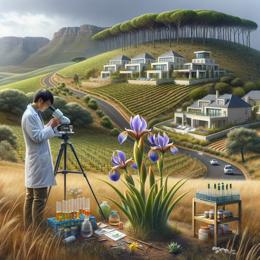

Image created by AI

Donkey-Powered Waste Management: Necessity Drives Innovation in Bamako's Trash Crisis

As the bustling streets of Bamako, Mali's sprawling capital, grapple with a growing waste management crisis, a fleet of donkey carts has emerged as an unconventional but critical element in the city's fight against refuse. Amid the towering piles of garbage that characterize Bamako's landscape, these humble carts, led by industrious collectors like Yacouba Diallo and his donkeys, Keita and Kanté, provide a lifeline to households desperate to dispose of their trash.

Diallo's story encapsulates the city's dire circumstances. With wages from his waste collection business reaching up to $165 per month, he represents the face of informal waste management in Bamako—a service not sanctioned by the state, yet indispensable to the population. Affordability reigns over automation, as donkey carts outpace motorized vehicles not in speed but in cost-efficiency and accessibility, especially in areas unreachable by cars.

At the chokepoints of Bamako's waste disposal system, sites like Badalabougou's dump serve as beacons of the city's inability to cope with the ever-expanding mounds of refuse. The arrival of collectors like Diallo is diligently noted in ledgers, underscoring the regimented nature of this informal sector, while simultaneously highlighting its separation from government oversight.

Mamadou Sidibé, overseeing the operations at the Badalabougou site, emphasizes the irreplaceable role of donkey carts. Even as he appreciates their utility in navigating narrow alleyways and rugged terrain, Sidibé, a waste management specialist and former city employee, starkly points to the concerning absence of state intervention—a gap leaving the city vulnerable to the adverse environmental and health consequences of inadequate waste disposal.

The rapid population boom in Bamako—more than doubling in recent years—exacerbates existing infrastructure insufficiencies. Criticism is levelled at the appropriate institutions for failing to construct operational landfills and waste processing facilities up to par with accepted standards. In the face of this institutional inertia, blame is deflected onto residents whom local authorities accuse of neglecting environmental and public health concerns, even as the garbage-scape continues to rise uncontrolled, threatening to engulf the city with no resolution in sight.

This gripping account of Bamako's makeshift waste management underscores a pressing need for investment in sustainable infrastructure, capable governance, and community engagement to tackle a problem that threatens the well-being of one of West Africa's key cities.