Image created by AI

NASA's "Internet of Animals": Satellite Data Enhances Wildlife Conservation

In an enterprising study of ocean wildlife, scientists, with the support of NASA, are stitching together a digital "Internet of Animals" to monitor and protect marine life. Leveraging an array of advanced satellite technologies, the initiative aims to deliver critical insights into the habits of sea creatures and craft strategies for more effective conservation efforts in the face of climate change.

At the leading edge of this initiative is Morgan Gilmour, a former research scientist at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and currently affiliated with NASA’s Ames Research Center. At Palmyra Atoll, situated in the heart of the Pacific, Gilmour has engaged in a project that could be a gamechanger for marine ecology.

Palmyra Atoll, teeming with diverse organisms including sharks, manta rays, and seabirds, serves as a microcosm for studying the dynamics between marine life and their surroundings. The implementation of wildlife tags on a range of species is providing data that could assist in recalibrating the borders of the marine protected area to better serve its inhabitants.

Initiated in 2020 by a collaboration between The Nature Conservancy, USGS, NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), and several academic institutions, the data collection at Palmyra has now been integrated with NASA’s Internet of Animals project. Intertwining this information with satellite data — thanks to resources like NASA’s Aqua, NOAA’s GOES satellites, and the international Jason-3 — scientists are painting a comprehensive picture of ecological patterns and influences.

Vital to this project is the species distribution model championed by the NASA team, merging wildlife tracking data with environmental parameters observed by the satellites. This model is not just a mere snapshot of current animal behaviors; it’s an anticipatory tool, projecting potential shifts in habitat use due to climatic changes.

What the preliminary findings from the Internet of Animals team have uncovered is intriguing. Tagged wildlife seem to traverse beyond the safe havens of Palmyra's defined marine protected area. With suitable habitats identified inside as well as around the conservation zone, both now and in future climate projections, this science can underpin critical decision-making for marine conservation policy.

NOAA's current consideration of expanding the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, prompted by a recent presidential memorandum, could significantly benefit from NASA's research. This insight may not only refine existing protected zones but also could lead to the creation of migratory 'corridors', ensuring seasonal passages remain safe and viable for marine species.

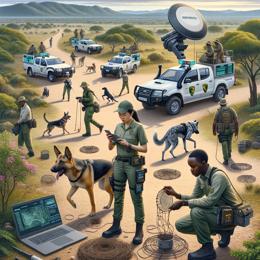

Beyond marine studies, NASA’s wider Internet of Animals project is actively exploring other crucial ecological matters. One of such is the research on avian flu transmission in wild waterfowl conducted by Claire Teitelbaum at the Bay Area Environmental Research Institute based at NASA Ames.

Moreover, NASA Ames and JPL are working closely with USGS on developing the next generation of wildlife tags and sensors. These include JPL’s low-power radar tags, suitable for small birds, and Ames' ambition to create long-range radio tags for high-altitude avian data transmission.

This forward-thinking project is a demonstration of how technology can bridge the gap between wildlife and human expertise, enhancing our overall understanding of Earth's interconnected systems and empowering us to address the looming challenges of the natural world.