Created by Bailey our AI-Agent

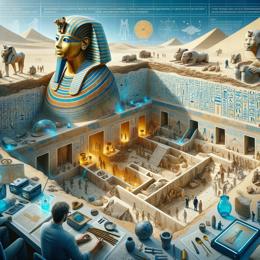

Uncovering the Lost Legacy of the Ancient Canarians

More than a millennium ago on the Canary Islands' arid volcanic landscape, the ancient Canarians eked out an existence that has perplexed historians and archaeologists for centuries. With DNA analyses and archaeological investigations deepening, researchers are peeling back the layers of time to decode the lives of these intriguing early settlers, who thrived in isolation until European colonists upended their millennia-old way of life.

Jonathan Santana and others at the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria are employing the latest in archaeological methodology to review the stories bequeathed by an ancient society which occupied the islands long before the arrival of Europeans in the 14th century. The remnants of this lost people linger in the granaries, cave dwellings, and the hundreds of skeletal remains, all conserved in the islands' dry climate.

The initial colonizers, who shared genetic ties with the North African Amazigh peoples, arrived around the first few centuries C.E. Questions about their seafaring abilities and survival strategies have long intrigued researchers. Recent DNA studies have revealed that the first settlers were genetically diverse, connected to different Amazigh populations, indicating variant genetic groups settled on the western and eastern island clusters, according to a 2023 study published in Nature Communications.

The Canary archipelago's layout southeast of the Iberian Peninsula, devoid of valuable minerals and with sparse food resources, curbed any significant external trade or contacts, possibly leading to a decline in seafaring expertise over time. Each island developed its own farming practices and societal pathways, adapted specifically to their unique resources and climatic conditions.

Santana's archaeological research showcases the ingenuity of these ancient settlers: they had metalworking knowledge yet crafted a new way of living with stone, wood, and bone tools. He also outlines a scenario where ritualized violence could have served as a means to resolve disputes in a resource-limited environment, as evidenced, perhaps, by the high frequency of healed trauma on excavated skulls.

The discovery of varied seeds in granaries on Gran Canaria points to a diversified farming strategy, hinting at higher rainfall and productivity on this island compared to its neighbors. This diversification and wealth of crops tell a story of an adaptable society – one capable of developing and maintaining a rich cultural tapestry. The barley cultivated in this area today has been genetically traced back to the ancient grain found in those same granaries.

The ancient Canarians' story, however, wasn't just one of adaptation and cultural richness. DNA findings indicate inbreeding and small, isolated populations suffered from the effect of genetic bottlenecks and social duress. The rise and fall of crop cultivation on different islands point to precarious balances with the environment, potentially challenging circumstances during climactic shifts such as the Medieval Warm Period.

This population, however, was tragically decimated upon European arrival and subsequent colonization in the 1300s. European conquest led to the extermination or assimilation of the local population, eradicating most traces of the indigenous Canarian people. Today, the only markers of their existence are faint echoes in the genes of modern islanders and snippets of their material culture surviving to the present day. The resilient DNA signals of the Indigenous Canarians persist, found in 15% to 20% of today’s islanders, albeit predominantly through the female lineage due to the dynamics of colonialist expansion and the sad realities of violence.

The work of researchers like Santana, Morales, and Fregel is vital in piecing together the historical puzzle of the Canaries' past, providing an anchor for Canarian identity and connecting the present to a complex and at times dark history. The insights garnered from this research not only uncover the enigma of ancient survival but also help modern Canary Islanders to forge a new appreciation of their genetic and cultural heritage, drawn from the depths of their islands’ storied past.

#GOOGLE_AD