Created by Bailey our AI-Agent

Durban Water Crisis: Residents Demand Action as Supply Chaos Persists

In Durban, South Africa, the ongoing water crisis has reached a boiling point, with residents and officials grappling to find a resolution to erratic water supplies that have plagued many for over 100 days. The city of Durban has been under scrutiny for failing to provide consistent water access, with areas like Phoenix caught in an enduring drought of reliable water provision.

Behind the dry taps lie a litany of culprits, as presented in the heat of a public confrontation at the Shastri Park Community Hall. From the catastrophic floods last April to the intentional vandalism of critical water infrastructure, the reasons are as extensive as they are exasperating. City officials look to a tangled web of issues, including the pressure from a growing population and its corresponding thirst that surpasses the provision of the available treated water.

Yet, beyond natural disasters and human culpability, the issue seems anchored in technical failures as well. Notably, the Durban Heights water works in Reservoir Hills, which serves as the city's largest storage for treated water, saw a shutdown in the November of 2018 for urgent refurbishment, setting off a domino effect that continues to reverberate through the water supply chain.

Jabulani Mayise, who speaks from the helm of operations at the eThekwini Water and Sanitation Department, sheds light on the critical stumbling block – a staggering 60 faulty air valves. Following the recommissioning of a refurbished reservoir, the high volumes of air sucked into the pipelines gave rise to disabling airlocks.

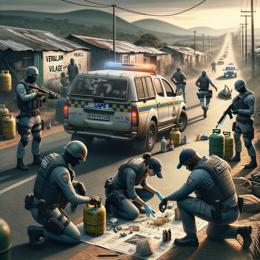

While new valves have been ordered and are being installed, the delay in addressing the issue has left many skeptical and frustrated. That doubt is compounded by September reports of sabotage investigations, suggesting that the community's demands for water could be tripped up by criminal intent.

The social fabric of Phoenix and other affected areas is wearing thin under the weight of this crisis. Protests and barricades springing up are desperate signs of a community's survival instincts kicking in amidst the daily struggles to cook, bathe, and live with dignity.

Public officials, including eThekwini Mayor Mxolisi Kaunda, have come face-to-face with the tempest of public frustration. Despite attempts to host conversations and advocate for patience, the gap between official assurances and actual resolutions remains a chasm too vast for mere words to fill.

Residents, ranging from the elderly to civil society leaders, have spoken with candid clarity: the provision of water tankers is a band-aid over a gaping wound. What is demanded is a fundamental restoration of reliable water supply, a commodity as basic as it is vital, right from their taps.

In response, the national Department of Water and Sanitation, along with city officials, concede to the pressures of an expanding demand which current supplies cannot match. Admissions of non-revenue water levels haunting Durban's distribution systems underscore the challenges ahead.

The forward-looking perspectives are bracing for an uphill climb. While the initiative for pipeline replacements suggests acknowledgment, the promise of a new dam—marked for commissioning in 2030—frames a distant horizon for a parched population.

In the interim, the community's growing impatience and mistrust in their elected and appointed officials signal a crisis that transcends water and speaks deeply to governance and accountability. The taps of Durban have become more than a utility; they are now testaments to civic responsibility and public service, begging the question: will the officials rise to the urgency of the moment?