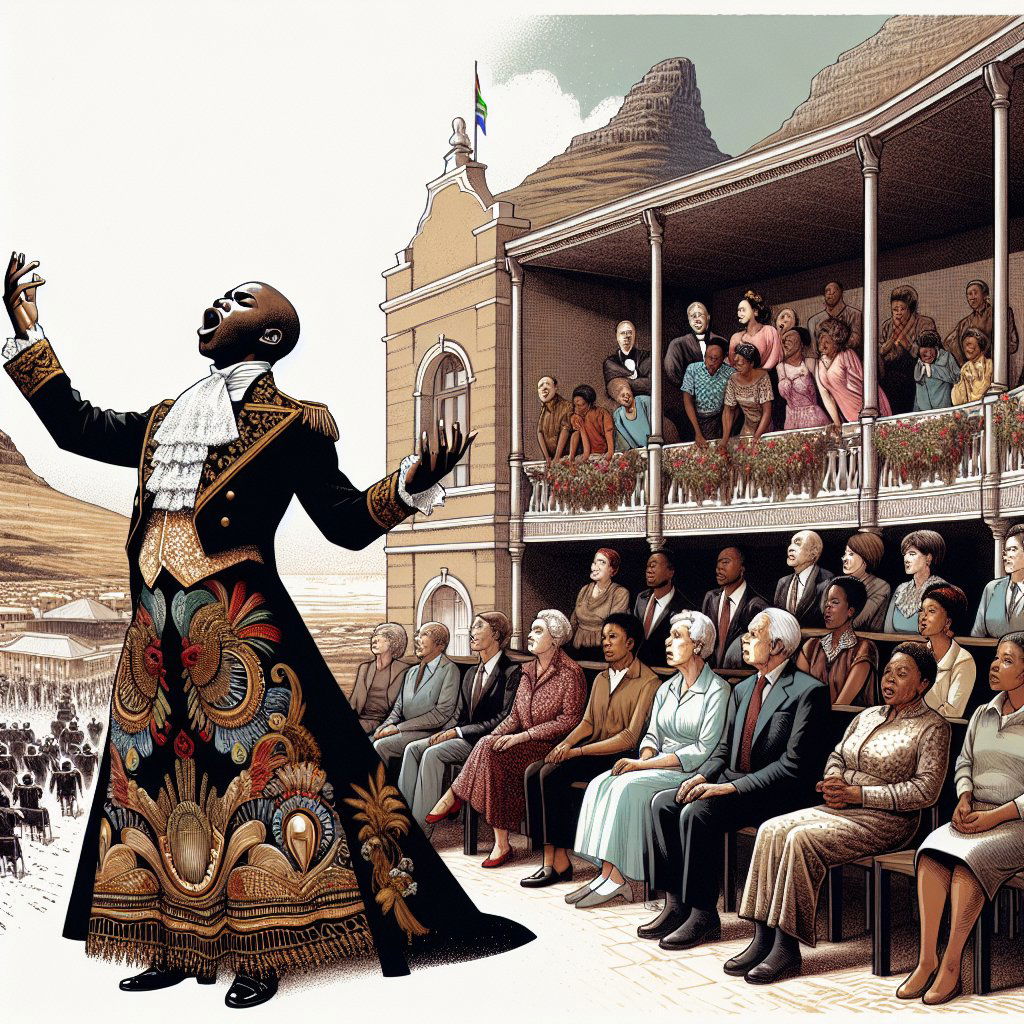

Image: AI generated for illustration purposes

Cape Town's Operatic Evolution: Embracing African Identity in a Colonial Art Form

In a dramatic turn that defies the expectations held at the end of apartheid, opera in South Africa has not only survived but evolved, embracing its African roots and flourishing in the process. Cape Town, in particular, stands at the forefront of this cultural renaissance, not just preserving the traditional western opera but reshaping it into something distinct and relevant to the South African context.

Wayne Muller's research on post-apartheid opera, covered in his book "Opera in Cape Town: The Critic’s Voice," reveals the critical role of newspaper critics in the transformation of this historically western art form. Muller, a foremost authority on the subject, meticulously traced the changing attitudes in opera reporting from the mid-1980s through the next three decades. Early on, the narrative resisted indigenous influences and coveted the survival of western opera, yet the discourse eventually shifted, prompting readers to accept the burgeoning reality of opera with a unique African influence.

Opera's journey in South Africa mirrors the country's own history. Introduced in the 1800s, it was a clear symbol of colonial influence, with European theatre companies bringing staples such as the French opéra comique. As the local scene developed, opera was professionalized through infrastructure like theatres and formal training for singers.

Post-apartheid, the Africanisation of opera manifested in multifold ways—most notably by translating western operas into local languages and relocating narratives to South African settings, such as in the reimagined "La Bohème Noir." More ambitiously, original South African compositions began to emerge, incorporating indigenous music and stories that speak to the nation's cultural heritage.

The appearance of black opera singers on the global stage is perhaps the most tangible evidence of this transformation. Initiatives such as Capab’s Choral Training Programme laid the groundwork for this development by increasing accessibility to vocal training for black singers. As a result, artists such as Pretty Yende and Levy Sekgapane have been celebrated at prominent international opera houses, signaling a triumphant breakthrough in representation and dismantling of past racial barriers.

Despite the significant strides in documenting and analysing the Africanisation of opera, Muller acknowledges the limitations inherent in the existing historical account. Archives still lack the breadth and depth needed to write a comprehensive history. The journey remains ongoing as further perspectives and sources emerge, but the book succeeds in capturing the pivotal patterns and trends documented by opera critics.

The transformation of opera in Cape Town is more than a mere cultural curiosity; it's a testament to the power of the arts to reinvent themselves, reflecting and shaping national identity. As the world continues to witness the rise of South African opera, it becomes clear that the survival of this art form lies not in its resistance to change but in its capacity to adapt and resonate with the spirit of its people.