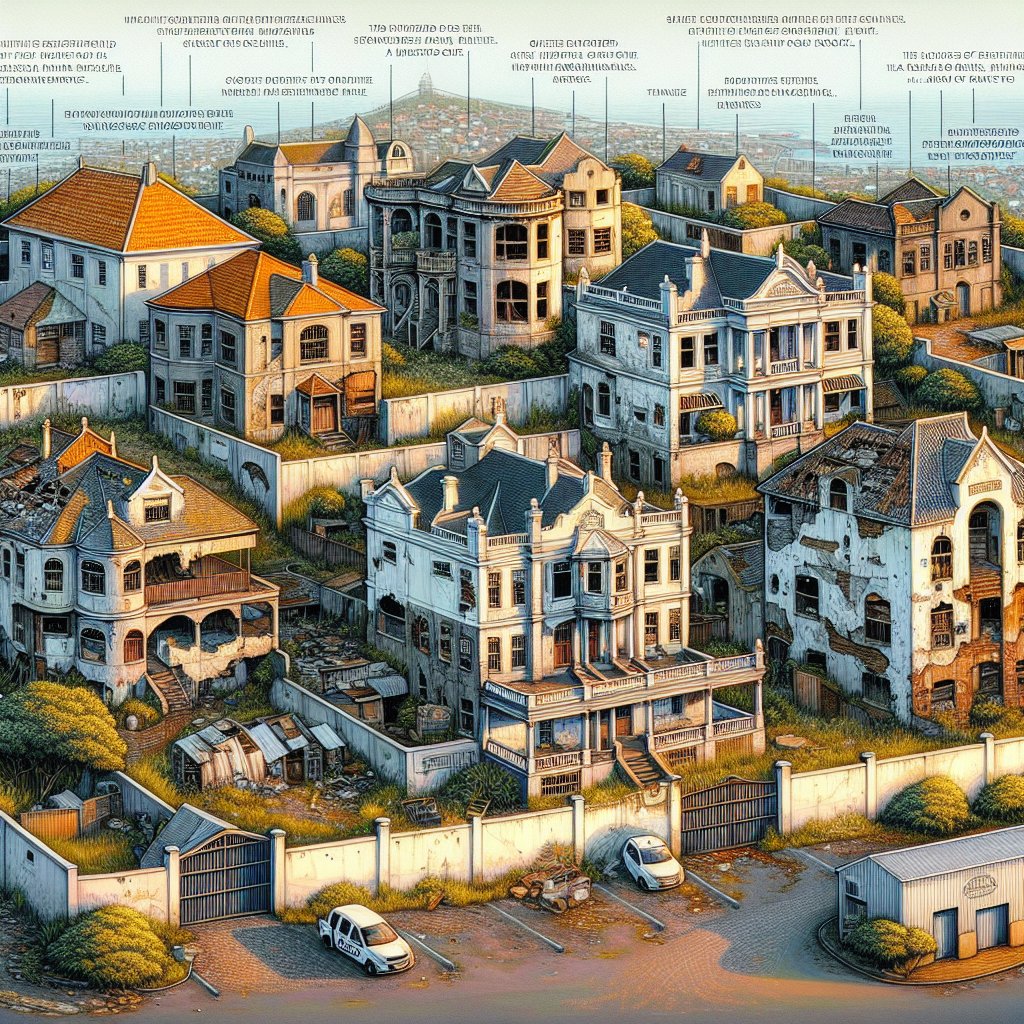

Image: AI generated for illustration purposes

Dereliction and Mismanagement: Waterloo Green's Neglected Heritage

The lush suburb of Wynberg in Cape Town is embroiled in controversy as the Department of Public Works and Infrastructure (DPWI) faces heavy criticism for the gross mismanagement of valuable property. The property, located in the historic area known as Waterloo Green, encompasses 21,000 square meters and is laden with buildings that carry an imprint of the past. Sitting idly, the land and these structures could tell tales from more than 150 years ago, however, now they speak of neglect and oversight.

At a portfolio committee meeting on Wednesday, Members of Parliament did not hold back their disapproval of the DPWI's failure to maintain this prime Cape Town real estate properly. The six-building property includes two homes that have been abandoned to the point of being gutted for wiring and plumbing, now serving as a haven for drug use. A protected double-storey heritage house stands mostly intact, and two residences have tenants but show significant wear and tear.

This debacle began when the South African Police Service (SAPS) returned the accommodation quarters back to the DPWI in 2016, which has since overseen the property's descent into disrepair. Ironically, the sixth building, a warehouse, still serves a vital role as a garage for SAPS.

Local residents, surrounded by premier schools and affluent areas like Chelsea Village and Maynardville Park, have petitioned to deal with the blight caused by two particularly derelict homes and are seeking answers from DPWI. These buildings are historical markers, and their heritage status complicates discussions about their future.

Penny Penxa, the DPWI regional manager, addressed the MPs with news of potential proposals for utilizing these properties, including interest from the Department of Defence and the Department of Justice but bemoaned the invasion and deterioration of these houses since they were returned by SAPS. She did extend an apology and noted that a security company had been hired and legal avenues were being pursued to evict illegal occupants.

The community's plight, voiced by Ward Councillor Emile Langenhoven, paints a grimmer picture with incidents of illegal dumping and occupation. Worse still, the failure to prevent these instances despite multiple pleas to the DPWI for intervention. This presented the housing opportunities lost and illustrated a broader systemic failure by government institutions to effectively manage public land, as emphasized by housing advocacy expert Nick Budlender from Ndifuna Ukwazi.

The frustration of the MPs signals a broader discontent that echoes beyond Cape Town. The DPWI was reprimanded for providing no clear timelines for the proposed actions and not supplying the mandatory written presentation to the committee. The MPs' sentiments were echoed in the promise by DPWI deputy minister Bernice Swarts to return to the committee with a comprehensive written plan, acknowledging that the policy for dealing with heritage sites might need clarification and adapting for situations like these.

Public land, especially with such rich history, requires responsible stewardship not just for preservation but to foster communities that are secure, aesthetically pleasing, and sustainable. The Waterloo Green crisis underlines the necessity for immediate action and restructuring within the DPWI to prevent further loss of potentially transformative land across South Africa. What stands at Waterloo Green should serve as a stark reminder of the core responsibilities held by our public departments. The portfolio committee plans to draft a report for further discussions in Parliament, with the hopes of resolving this long-standing issue.